Peru Banknotes 10 Intis banknote 1985 Ricardo Palma

Central Reserve Bank of Peru - Banco Central de Reserva del Perú

Obverse: Portrait of Ricardo Palma at right, Coat of arms of Peru at center, denominations below coat of arms. Treasure of the Inca - Ceremonial Knife (Tumi) at lower center.

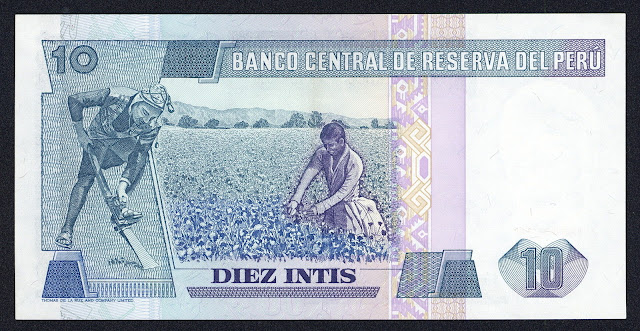

Reverse: Indian farmer digging at left, Peruvian woman picking cotton at center.

Watermark: Ricardo Palma.

Printer: Thomas De La Rue & Company Limited, London, England.

Original Size: 150 x 75 mm.

Peru Banknotes - Peruvian Paper Money

1985-1991 "Inti" Issue

The inti was introduced on 1 February 1985, replacing the sol which had suffered from high inflation. One inti was equivalent to 1,000 soles. Coins denominated in the new unit were put into circulation from May 1985 and banknotes followed in June of that year.Ricardo Palma

Ricardo Palma (born February 7, 1833, Lima, Peru — died October 6, 1919, Lima), Peruvian writer best known for his collected legends of colonial Peru, one of the most popular collections in Spanish American literature.

At age 20 Palma joined the Peruvian navy and in 1860 was forced by political exigencies to flee to Chile, where he devoted himself to journalism. Six years later he returned to Lima to join the revolutionary movement against Spain. He also took part in the War of the Pacific (1879–1883; it arose between Peru and Chile as a dispute over territory) and during the Chilean occupation courageously protested against the wanton destruction of the famous National Library by Chilean troops. After the war Palma was commissioned to rebuild the National Library; he remained its curator until his death. In 1887 he founded the Peruvian Academy, a learned society.

Palma’s literary career began in his youth with light verses, romantic plays, and translations from Victor Hugo. His Anales de la inquisición de Lima (1863; “Annals of the Inquisition of Lima”) was followed by several volumes of poems. His fame derives chiefly from his charmingly impudent Tradiciones peruanas (1872; “Peruvian Traditions”) — short prose sketches that mingle fact and fancy about the pageantry and intrigue of colonial Peru. His sources were the folktales, legends, and pungent gossip of his elders, in addition to historical bits gleaned from the National Library. The first six volumes of this series appeared between 1872 and 1883; they were followed by Ropa vieja (1889; “Old Clothes”), Ropa apolillada (1891; “Moth-Eaten Clothes”), Mis últimas tradiciones (1906; “My Last Traditions”), and Apéndice a mis últimas tradiciones (1910; “Appendix to My Last Traditions”). A series of racy legends, Tradiciones en salsa verde (“Traditions in Green [Piquant] Sauce”), were published posthumously.

Ceremonial Knife - Tumi

Gold with turquoise inlay: 34 x 12.7 cm (13 3/8 x 5 in.), A.D. 1100/1470

Naymlap, the heroic founder-colonizer of the Lambayque valley on the north coast of Peru, is thought to be the legendary figure represented on the top of this striking gold tumi (ceremonial knife). The knife would have been carried by dynastic rulers during state ceremonies to represent, in a more precious form, the copper knives used for animal sacrifices. Here Naymlap stands with his arms to his abdomen and his feet splayed outward. His headdress has an elaborate open filigree design and is festooned with various small gold ornaments. Turquoise—for the peoples of ancient Peru, a precious gem related to the worship of water and sky—is inlaid around the headdress and in the ear ornaments. The tumi was made with diverse metalworking techniques. Solid casting was used to produce the blade. The face and body were created with annealing (heating, shaping, and then cooling) and repoussé, in which the design is hammered in relief from the reverse side. Finally, the small ornaments at the top of the headdress were separately hammered or cast, then soldered into place. This tumi and many other gold, silver, and textile objects were made in royal workshops and ceremonially presented to high officials as emblems of rank and authority.